The rebirth of tintype: an old photographic medium is revitalized

Three artists talk about their work in a traditional process.

Eastern Sierra view

In a time when photos are produced quickly and then forgotten, and when almost everyone has a camera and gigabytes’ worth of images in their pockets, it’s no wonder that some of the most interesting photographers today are slowing down. Way down.

Tintype, a kind of wet-plate process whereby chemicals are applied to metal and then an image is exposed directly and developed on the spot, is experiencing a resurgence. The Rayko Photo Center in San Francisco, the Eastman Museum in Rochester, and the Penumbra Foundation in New York are only a few organizations across the U.S. where photographers are signing up to learn the methods of their forebears.

We asked three artists who have built careers on this decidedly old-fashioned medium what drew them to it and why artisanal photography couldn’t have come along at a better time.

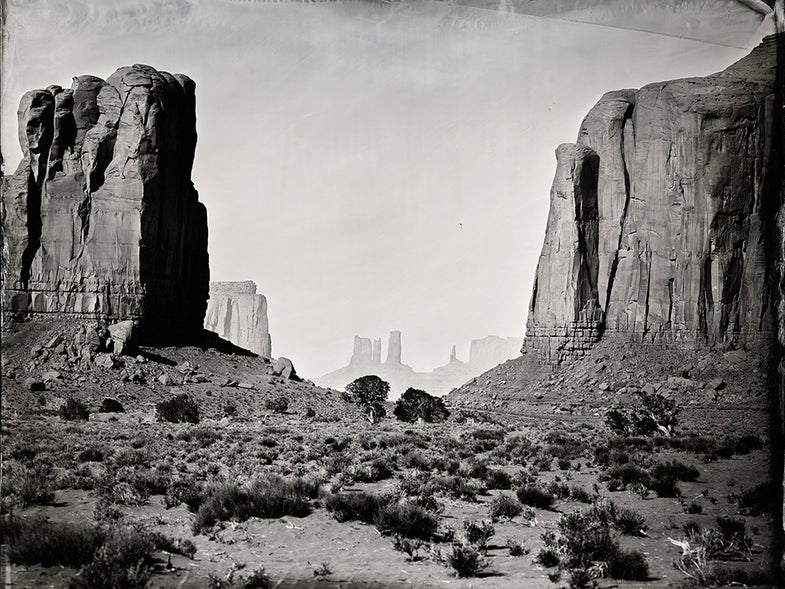

John Wayne’s special spot

Ian Ruhter

Ian Ruhter had a good 10-year run as a Los Angeles commercial photographer, but he paused when the work demanded he go exclusively digital. The idea of manipulating images in postproduction troubled him. “I thought it was really wrong and I didn’t want to be remembered for it,” Ruhter recalls.

At the same time, using a digital camera to make street portraits was just as troubling: The camera sparked confrontations with his subjects, who seemed, he says, to feel exploited. So he started going out with an old Polaroid Land Camera and handing out Polaroid prints to the people he photographed. Rather than simply take pictures, he was actually connecting.

Then Polaroid film was discontinued. Reasoning that even if every company that made film went out of business, he could still make his own, Ruhter decided to explore wet-plate photography. He sought out William Dunniway, a wet-plate photographer and educator, and began studying with him around 2009.

Commissioned picture

Ruhter resonated with the people who made wet-plate photographs in the 19th century, who, he says, “were on the forefront of art, science, and exploration.” He had found the medium he had always been looking for.

Within months of making his first tintypes, Ruhter quit commercial photography. He wanted not only to work in tintype full-time but also to push the medium. “I wanted to see a wet plate as never seen before,” he says. His goal: 4×5-foot tintypes.

That meant building a giant camera. So Ruhter bought a truck, found a lens on eBay, and began. One of the biggest challenges was figuring out how to fit it all in the truck and build a mechanism to operate the camera. He eventually realized that he himself needed to be part of the camera rather than using machinery to move the plate, open the lens, focus, and so on. “That day was the game changer,” Ruhter recalls. “I can rely on myself, I can do all the movements and steps and have the ability to change things on the spot. I was looking at it from the inside of a camera at this point—and that changed everything.”

Early work

Ruhter orders the metal plates in bulk, then cuts the 4×8-foot sheets to size at a nearby machine shop—whether it’s for a 27×35-inch plate (which is still very large for a tintype) or his 4×5-foot plates, a goal he reached in 2011.

With all his achievements in building this giant camera, Ruhter still thinks of Will Dunniway, the man who introduced him to tintype. “After I made a proper exposure and held the plate in my hand, I thanked him. I held the physical knowledge to make these myself. It was one of the greatest gifts I’ve ever been given.”

A range of faces

Kari Orvik

While photographer and artist Kari Orvik’s storefont studio, with its strobes and backdrops, may resemble those of other photographers, Orvik’s is set up for tintype portraits, and her clients come to her specifically to have their likenesses made in this unique medium.

After studying photography in college, Orvik took a tintype workshop with Michael Schindler at the Rayko Photo Center in San Francisco. Schindler, who cofounded the retail store and tintype studio Photobooth, asked Orvik to come work with him as a photographer there. After Photobooth closed, Orvik opened her own eponymous tintype portrait studio in 2014.

Portrait of a pair

Orvik was drawn to the wet-plate technique because she didn’t want to spend time in front of the computer processing images. “It’s helpful to slow down and look at each image one by one” rather than being bombarded by multiple digital images that you quickly scroll through, Orvik says.

She also likes tintype because in both process and product it keeps the experience of photography physical. And because of the medium’s longevity, her clients have something to pass down to future generations. Orvik explains that most people who come to her studio come to mark a milestone such as a birthday or an engagement; she points out that a tintype engagement photo offers an alternative to the typical sunset-on-the beach photo shoot. Some clients have tintypes from generations past and want to add their own image to a family tintype album.

A poet outdoors

Orvik finds something timeless, or time-traveling, perhaps, about tintype. When she brought her setup to her 20-year high school reunion in Fairbanks, Alaska, she says, “I hadn’t seen [my classmates] in many years, but when I put my head under the focusing cloth, it was like going back and seeing them when they were 18. It was like being in the past and the present at the same time.”

Musician portrait

Lisa Elmaleh

Lisa Elmaleh’s love of photography began at an early age as she peered over the edge of the sink watching her father develop images in the darkroom. She started shooting her own pictures with a little 110 camera and eventually graduated to an 8×10 camera as a BFA student at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. There Elmaleh took an alternative process workshop with photographer Christopher James, author of The Book of Alternative Processes. Attracted to the historical work of William Henry Jackson and Julia Margaret Cameron, Elmaleh says that after the workshop she “fell in deep.”

“My interest in historic processes,” Elmaleh explains, “was that I was making prints by hand—I was in the darkroom, working from scratch—making my own chemistry and painting on the emulsion. That appealed to me.”

Band in the water

Since learning the wet-plate process in 2007, this West Virginia–based artist has traveled the country with her darkroom, first carrying it in the trunk of her car and then in a truck tricked out with a bed.

For Elmaleh, there’s a deep connection between the tintype process and her series American Folklife, a group of environmental portraits of Appalachian musicians. She points out that historically tintypes democratized photography as an affordable and accessible process. Appalachian music is similarly democratic, she says: “It’s a community gathering, a community event—you get together and you play music.”

Working in 8×10, her camera of choice is a Century Universal, which she describes as a less expensive version of a Deardorff. It folds down into a neat little box and weighs about 8 pounds, which is very light for this format. But, she adds, her lens—a Schneider Kreuznach 300mm—weighs almost twice as much. “I’ve tried other lenses,” she says, “but I always go back to this one. Maybe it’s because I’m so familiar with it that I know what it’s going to do and what it’s going to look like. It’s really soulful—it’s got something to it that I can’t explain.” Her dark box is a simple handmade cardboard enclosure with fabric that she wraps around herself.

Mandolin detail

When photographing the musicians, Elmaleh usually visits their homes and spends the entire day with them. She generally parks her truck under a tree and has them pose in the open shade. From start to finish, the process of creating a tintype takes her about 30 minutes. While Elmaleh is working in the dark box, the musicians are outside playing their instruments. “You’re working, they’re working—everyone’s collaborating,” she says