Cindy Sherman’s self-portraits and 5 other photo exhibits worth seeing right now

A list of photography shows taking place at museums and galleries throughout the US in early 2022, including work by Bruce Davidson, Nikki S. Lee, Alec Soth and more.

Self-portraiture is one of the most elastic genres. The proof is that it’s been in the visual arts for centuries, since at least 1498 when Albrecht Durer revealed to the world his oil-painted selfies. We had to wait until 1839 to get the first photographic self-portrait, by Robert Cornelius. But after that, photographers and artists have used—and are continuing to use—all sorts of processes, both analog and digital, to capture self-portraits.

I have an agenda, of course, in bringing up selfies: There are currently two intriguing fine-art photography shows, both in New York state, that in one way or another, relate to self-portraiture, or at least to the notion of “the self”.

The first, a group exhibition called “Alter Egos | Projected Selves,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York City, presents a wide range of self-portraits types. And even includes some work that seemingly doesn’t fit the self-portrait category at all.

The second show, “I Believe I’ll Run On,” features up-and-coming artist, Joshua Rashaad Mcfadden (b. 1990), at the George Eastman Museum, in Rochester, New York. There are no self-portraits in this show, rather, Mcfadden explores the concept of the self by looking to others. As a young African American artist, his work examines the racism and anti-Black violence that Black Americans have and continue to experience, from slavery to the present day. His work also touches on other topics including masculinity, sexuality, and gender.

You can find out more about each of these intriguing shows, and several others, below.

“Alter Egos | Projected Selves”

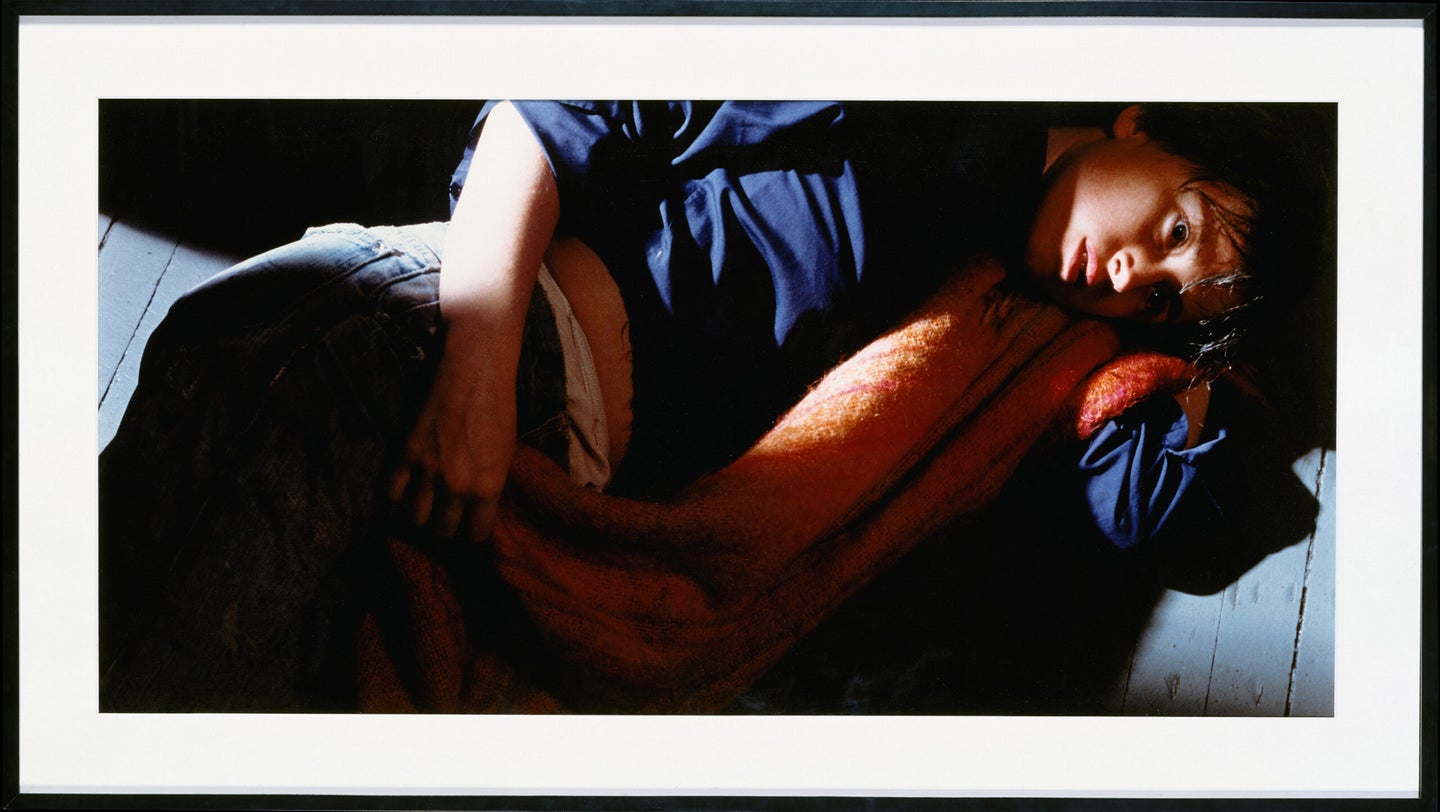

One critical element of this group show that’s refreshing to see—at least when it comes to self-portraits—is that it presents work by artists engaged in a variety of self-portraiture creation strategies. Take the B&W photo, “Down Stairs,” by German commercial and documentary photographer Elisabeth Hase (1905-1991), who captured it sometime in the late 1940s. What’s intriguing to see is that Hase’s self-portrait depicts the photographer after she has apparently tripped or perhaps thrown herself face-down on a flight of stairs. It reveals how Hase was actually experimenting with staged scenarios almost a full 30 years before Cindy Sherman (b. 1954)—who’s also in the show—began her first series of groundbreaking self-portraits, with her “Untitled Film Stills” series.

Sherman is undoubtedly one of the most influential artists alive, at least for conceptual artists and photographers. So, it’s not surprising that she is the keystone in this show, as well, since her entire oeuvre embodies the notion of alter egos and projected selves. It’s almost tempting to talk about some of the other work in the show and call the approach “Sherman-like.”

A highlight of the show is South Korean artist Nikki S. Lee (b. 1970). Her images are part of her powerful series, “Projects (1997–2001)”, which comprises photographs of herself appearing as different groups of people, including punks, swing dancers, hip-hop musicians, skateboarders, young urban professionals, schoolgirls, and many more. Each image in this series was captured on a simple point-and-shoot camera, and taken by someone else. So, while her work shares some similarities with Cindy Sherman’s photography, she carries the process further by trying to integrate herself into these various subcultures and then, in a way, collaborate with them, since she doesn’t shoot the photo.

There are other inventive approaches to self-portraiture included in this show, like the artwork of Debbie Grossman (b. 1977), which, at first, don’t seem like self-portraits at all. Grossman uses the power of digital imaging and photo manipulation to invent a striking new narrative on the fluid nature of gender. The three images in the show are based on the work of Depression-era photographer, Russell Lee, who worked for the Farm Security Administration in the 1940s and documented a small community of homesteaders in Pie Town, New Mexico. In 2010, Grossman appropriates Lee’s photos and reworks them using Adobe Photoshop software (which she considers her primary medium) and creates an alternative Pie Town, one that’s inhabited exclusively by women. So, Grossman’s photos are in the show because it’s her fantasy or vision, or concept—“to make the history I wish was real”—that you might consider a self-portrait.

In her artist statement on her 2010 “Pie Town” project, Grossman describes her intentions: “Russell Lee… felt Pie Town represented a kind of hardy, small-town community that was disappearing in America. His pictures of the town are tinged with his mythologizing of a difficult way of life and the land-conquering kind of patriotism that’s a foundation of the American story. I share Lee’s nostalgia. Seventy years later, I am drawn to a similar utopian ideal. I’m filled with a longing to connect with that time and the people in Lee’s images—I’ve had a lifelong obsession with frontier life. I fantasize about locating myself within those pictures and that time. So in an attempt to make the history I wish was real, I have made over Pie Town to mirror my fantasy.”

Where: The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

When: November 22, 2021–May 1, 2022

For more info on the exhibition, go to the museum’s website at Metmuseum.org.

Joshua Rashaad Mcfadden: I Believe I’ll Run On

The photography exhibition, titled “Joshua Rashaad Mcfadden: I Believe I’ll Run On,” currently on view at the George Eastman Museum, is called an “early-career survey,” which is really another way of calling it a retrospective, which seems somewhat premature for a photographer only in his early 30s. Nevertheless, it showcases a lot of powerful work.

The show includes images from one of Mcfadden’s first projects, a series he calls, “Come to Selfhood,” from 2015-2016. Each part of the series is made up of three visual elements: a photographic portrait of an African American male subject taken by Mcfadden, which the artist places next to a photo of the subject’s father or father figure, and handwritten texts in which the subject shares stories of his life with the viewers.

At first glance, the three disparate elements fit together in an awkward manner. The photographs seem to distract from the text. And the photographs themselves seem to visually clash with each other since one is a highly crafted professional portrait and the other is often a slightly faded candid shot. But the more I looked at them, the more my eye made the connections between the three visual elements. I even started to think of how the format Mcfadden uses actually evokes other well-known formats in our memory, which also often have competing visual elements, like newspaper or magazine layouts, pages from a yearbook or wedding album, and many website pages we visit on the Internet.

Mcfadden says he included text in his work not so much for a visual effect, but for another reason: “I include a lot of handwritten texts in my work because I think that it gives another level of agency and humanity to the people I photograph…who sit for portraits for me,” says Mcfadden, in a video on the museum’s website. “I want them to be able to collaborate in the making of the final piece of the work.”

It’s heartening to hear such a sentiment from an artist, and I think it’s that kind of vision and generosity that will cement Mcfadden as a truly great visual artist.

What I also love about the “Come to Selfhood” works is that even at the young age of 25, Mcfadden is grappling with big ideas in a work of art. In fact, he was thinking about even bigger questions. When he created this unique series of portraits, Mcfadden actually presents a couple of questions, which begin his artist statement, “How does one begin to challenge the misguided perceptions that decrease the quality of living for young African American men? Furthermore, how does the African American man position himself in a society that does not acknowledge his true identity?”

The figures in the “Come to Selfhood” don’t have the answers to those questions, but they seem to be visually confronting you, asking the same questions and looking at you to engage in a conversation.

For those of you who can’t get to Rochester to see “Joshua Rashaad Mcfadden: I Believe I’ll Run On,” if you visit the website, you can see a virtual 360-degree tour of the exhibition.

Where: George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY

When: November 5, 2021–June 19, 2022, Main Galleries

For more info on the exhibition, go to the museum’s website at Eastman.org.

Alec Soth: A Pound of Pictures

Whether I’m listening to Alec Soth (b. 1969) speak on a Youtube video or podcast, or simply looking at his many inventive images, I find the artist fascinating. He has a Walker Evans-type of outlook on the world that’s addictive. He also has an incredibly alluring way of being casually compelling.

It’s why I’m excited to see his upcoming show, “A Pound of Pictures,” an exhibition of 16 large-format works photographed by Soth between 2018 and 2021, which will be appearing at three different galleries across the U.S. starting in mid-January 2022 and ending at the end of March (see below for exact dates).

But you might be wondering what the title of the show refers to. Soth says it came from an encounter with a vendor in Los Angeles who sold photographs “by the pound.” However, it’s great to hear how Soth describes it, in his own words, in a video about the work: “While making this work, I looked at a lot of pictures. I also collected a lot of pictures. And then finding out who are these people that have photographs. I’d go to flea markets, go on eBay, and I would gather these objects and just look at them and think about this medium, about what it means to be a photographer, and the different ways in which photographs live in the world. This desire to memorialize life when life is just going to keep whipping on by.”

He continues on in the same wonderful, slightly rambling way, “For me, photography has always been this physical act. It’s carrying this big box out into the world and trying to capture this image on this sheet of film, this substance that has to be developed. And one of the things I started thinking about is the weight of these pictures, the accumulated weight of them, as they sit in my archive and as they sit out there in the world. And I found this person in Los Angeles who sold photographs by the pound. And I thought, ‘Wow, how strange.’ And it’s like selling fish or something.”

Soth goes on to discuss other aspects of creating this work, like wanting to communicate the feeling of the weight of history, the weight of time. (You can listen to the rest here.)

As he says in the video, he’s come to the point where he’s paying attention “to my own attention.” It will be intriguing to see how that strategy plays out in the new photographs.

Where and when: The exhibition is taking place concurrently in three different locations throughout the U.S.:

- Minneapolis: Weinstein Hammons Gallery from January 28 – March 26, 2022

- New York: Sean Kelly Gallery from January 14 – February 26, 2022

- San Francisco: Fraenkel Gallery from February 3 – March 26, 2022

For more info on the exhibition, go to the gallery’s website at weinsteinhammons.com.

Aaron Siskind: Mid Century Modern

This exhibition focuses on some of the fascinating, inventively derivative images Aaron Siskind (1903-1991) made during the late 1940s and 1950s, which coincides with a time when he was interacting with a number of the major figures of mid-twentieth-century painting. It concentrates on a pivotal period when Siskind had a keen interest in abstraction and abstract painting.

It’s why I call them derivative, but perhaps a more useful term would be “influenced by” or “inspired by.” What’s important about the work and the show is that it puts on display the moment when the art from another visual medium became incredibly important to this photographer, and how he chose to infuse his photography with this new point of view and a new way of creating a photograph.

Where: Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego

When: Oct. 3, 2021–May 3, 2022

For more info on the exhibition, go to the museum’s website at mopa.org.

André Kertész: Postcards from Paris

This exhibition is dedicated to the formative years that photographer André Kertész (1894-1985) spent in Paris. This was a time when the photographer was printing photographs on a small, intimate scale. In other words, he was producing works that were about the size of a postcard. They may be small, but the works he produced at this time include some of the most iconic images in the history of modern photography.

Kertesz arrived in Paris in the fall of 1925, with not much more than his cameras. But by the end of 1928, he was contributing regularly to magazines and exhibiting his work internationally alongside well-known artists like Man Ray and Berenice Abbott. Creating small-scale photographs suited Kertész, for practical reasons: It meant he could carry his prints throughout Paris, share them with artist friends and potential patrons at the café table, or mail them to faraway family members as evidence of his increasing skill and professional success. It’s why the show pays careful attention to the works as both images and objects, emphasizing their experimental composition and cropped formats.

“Although André Kertész is one of the key figures of 20th-century photography; most people don’t know the depth of his work from this period,” said Elizabeth Siegel, the exhibition’s curator. “I’m thrilled to offer the public the chance to view these rare prints together.”

Where: The Art Institute of Chicago in Chicago

When: Oct 2, 2021–Jan 17, 2022

For more info on the exhibition, go to the museum’s website at Artic.edu.

Collection Close-Up: Bruce Davidson’s Photographs

The Bruce Davidson (b. 1933) photographs chosen for this exhibition were made between 1956 and 1995 and are primarily drawn from approximately 350 of Davidson’s photographs in the Menil Collection. Many of them have never before been on view.

What’s striking about Davidson’s photographs is they often depict an intimate perspective of his subjects and their communities, from circus performers to Welsh miners to New York City neighbors. “Davidson’s work is representative of how photography has and continues to be a crucial medium for social engagement,” said Molly Everett, curatorial assistant of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Menil Collection.

The show includes work from one of Davidson’s earliest and most powerful series, “Brooklyn Gang, 1959.” It also includes Davidson’s work from when he joined the Freedom Riders, who were college-age activists confronting racial segregation in the American South in the 1960s. The experience had a profound impact on the photographer. “Riding on that bus with the Freedom Riders,” said Davidson, “I became sensitized, and the exposure developed my perception.” One of his most iconic photographs comes from this march. It depicts a young man with a painted face, with the word, “VOTE,” inscribed across his forehead.

The remarkable images had an impact, as well, according to John Lewis, a leader of the Freedom Riders, who later became a United States Congressman: “Bruce’s courageous photographs helped to educate and sensitize individuals beyond our southern borders. They shone a national spotlight on the signs, symbols, and scars of racial segregation.”

Where: The Menil Collection in Houston

When: Dec. 10, 2021, through May 29, 2022. For more info on the exhibition, go to the museum’s website at Menil.org.